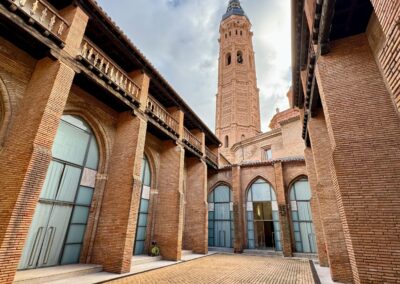

15. The Cloister, tower and apse of Santa María la Mayor

15. The Cloister, tower and apse of Santa María la Mayor

The Muslim influence left a deep mark on Calatayud after the conquest by Alfonso I the Battler in 1120, particularly in the splendour of the local Mudejar art. This artistic legacy can be appreciated in the Collegiate Church of Santa María la Mayor, whose main construction dates from the beginning of the 17th century, but which integrates valuable Mudejar elements from previous periods. In fact, its apse, tower and cloister were recognised by UNESCO as outstanding examples of Aragonese Mudejar art, receiving the designation of World Heritage Site in 2001.

The cloister is the oldest part of the complex and is possibly a vestige of the old main mosque. Its peculiar rectangular floor plan, with a length that is twice its width, distinguishes it from other traditional square-plan cloisters. Significantly, its major axis has a rotation of 30 degrees with respect to the church, orienting itself towards the southeast in the direction of Mecca.

A decisive moment in the history of the cloister occurred in 1415, when, by means of a papal bull issued by Pope Luna (Benedict XIII) and thanks to the generosity of Miguel Sánchez de Algaraví, an aristocrat from the town of Calatayud, a General Study was established there. This date coincides with the reform that gave rise to the current ribbed vaults. In its original configuration, the cloister had twenty-nine bays distributed in ten along its length and five across, with a double row in the southwest. However, the reorientation of the church in the 17th century meant the elimination of two bays on the south side, leaving it reduced to twenty-seven. The keystones that join the ribs of the vaults are mostly decorated in the flamboyant Gothic style, with the exception of two that show clear Islamic influence.

The cloister doorway stands out for its elaborate decoration at the entrance to the church, featuring a tympanum with 15th-century plasterwork and three sculptures of angels bearing shields with symbols related to water and fire. These iconographic elements are linked to the Platonic worldview about the structure and functioning of the universe, a conception that had a great influence on later philosophical and scientific thought. On the keystone that closes the vaulted entrance to the cloister of the collegiate church, the letter ‘B’, the symbol of Benedict XIII, can be seen.

Both the date and the style of the keystones suggest that the master responsible for this remodelling was Mahoma Ramí, who also worked on the now disappeared church of Saint Peter Martyr under the patronage of Pope Luna.

On the southwest side is the primitive chapter house, which possibly dates back to the second quarter of the 14th century, prior to the aforementioned reform. Its doorway, made of black alabaster from Fuentes de Jiloca, follows the Cistercian design, with geminated windows on the sides. These windows have a tumid arch (pointed horseshoe), an element that is not very common in Mudejar art and which probably imitated some Arabic model that has since disappeared.

Finally, towards the first quarter of the 17th century, a new chapter house was built at the north-western end of the courtyard, the lunette vaults of which are richly ornamented with baroque plasterwork featuring interlacing, and a second floor was added to the complex.